British Suakin Expedition Victorian 1854 Pattern Grenadier Guards Officer's Sword of Captain & Lt. Col. Ambrose Ayshford Goddard

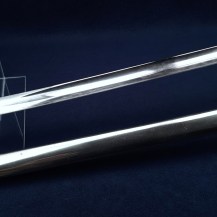

Slightly curved spear-pointed blade with central fuller. Pierced steel hilt of ‘Gothic’ style with inset regimental badge of the Grenadiers, a flaming grenade with shamrock, rose and thistle. Steel ferrule, smooth backstrap with chequered thumbrest, integral stepped oval pommel cap with tang button. Wire-bound black shagreen grip. Steel scabbard with two hanging rings & frog loop on upper band.

The blade is etched on one side at the ricasso with the maker’s mark ‘HENRY WILKINSON PALL MALL LONDON’ above which is the Prince of Wales’s badge of three feathers through a crown and a scroll reading ‘BY APPOINTMENT’. Moving up the blade on that side it is etched with battle honours of the Grenadier Guards within scrollwork, arranged chronologically: LINCELLES, CORUNNA, BARROSA, PENINSULA, and WATERLOO. Above these are a wreath of laurel and palm and the crown & cypher of Queen Victoria (in its mirrored form).

The other side of the blade is set at the ricasso with a brass proof slug stamped with ‘HW’ for Henry Wilkinson, within an etched six-pointed star. The blade is further etched with foliate motifs, an empty shield perhaps intended as space for optional owner’s initials or a family crest, and another group of battle honours in scrollwork: LIMA, INKERMAN and SEVASTOPOL.

This is a somewhat truncated list of the Grenadier’s honours to modern eyes, but it is correct for the period the sword was purchased because a number of honours for earlier battles were awarded to the Grenadiers retrospectively: Blenheim, Ramillies, Oudenarde, Malplaquet and Dettingen were awarded by the Alison Committee in 1882, Tangier 1680 and Gibraltar were awarded in 1909, Namur 1695 was awarded in 1910 and Egmont-Op-Zee some time after 1910.

The top of the hilt is stamped next to the blade with ‘5’. The spine of the blade is stamped with the serial number ‘15919’, which would date its sale to 1868. Wilkinson’s company records confirm that this sword, a ‘Medium Guards Sword’ was sold to ‘Ambrose Goddard Esq.’ on the 18th September 1868. Sevastopol was the most recent battle honour at the time of this sword’s production.

Ambrose Ayshford Goddard was born in 1848 in Belgravia, London. He was the eldest son of the main line of the Goddard family, lords of the manor of Swindon since 1563 with the family seat at Swindon House, known after 1850 as The Lawn, and extensive lands across Wiltshire which developed into interests in canals and railroads. The previous three generations (all of them named Ambrose) had all served as Members of Parliament including his father, Ambrose Lethbridge Goddard, who was the MP for Cricklade for the Conservative Party from 1847-68 and again from 1874-80. His uncle John Hesketh Goddard reached the rank of Major in the 14th Light Dragoons and was a veteran of the Second Anglo-Sikh War of 1848-9, taking part in the cavalry charge at the Battle of Ramnagar in which the 14th took heavy casualties, and the ensuing Battle of Chillianwala.

Ambrose purchased a commission in the Grenadier Guards on the 16th September 1868 at the rank of Ensign and Lieutenant. His date of commission matches up perfectly with this sword’s purchase date perfectly – swords were generally purchased by a new officer upon commission along with their uniform and he evidently went shopping only days after his position was confirmed.

Double rankings like ‘Ensign and Lieutenant’ were a peculiarity of the rank structure in the Foot Guards at that time: all officers in the British Army gained their commissions by purchasing them, but commissions in the Foot Guards were so desirable that they commanded a significantly higher price than those of other regiments. If an officer were to later transfer out of the Guards to another regiment where the same rank was cheaper he would effectively lose the premium he paid, therefore an Ensign in the Guards was entitled to transfer to another regiment at the rank of Lieutenant, a Lt at Captain and so on. A Captain in the Guards, provided higher-ups agreed on his competence and suitability, could transfer to immediately command a whole line infantry regiment.

Ambrose would be one of the last Guardsmen to enter into this system, as the purchase of commissions was abolished in 1871, the same year he purchased the rank of Lieutenant and Captain. Men holding a double rank appear to have been grandfathered in to that system even after the system changed, however, so he remained Lieutenant and Captain then was promoted to Captain and Lieutenant-Colonel in 1879, serving with the 3rd Battalion.

This battalion formed part of General Graham’s ‘Suakin Field Force’ during the Mahdist War in Sudan, a conflict which had been ongoing since 1881, when Sudanese religious leader Muhammad Ahmad bin Abdullah declared himself to be the Mahdi or messiah of Islam and amassed an army of followers with which he challenged the rule of the Khedivate of Egypt over Sudan. From 1882 Egypt was effectively administrated by the British as a result of the Anglo-Egyptian War so the rapidly spiralling situation in the Sudan, which threatened multiple Egyptian garrisons stuck in increasingly hostile territory, became their problem.

The British tasked General Gordon to effect a withdrawal of remaining Egyptian forces, but he ended up cut off and under siege in Khartoum, with nearly every tribe in the region siding with the Mahdi. Gordon deliberately refused to leave, effectively forcing the British government, which had little interest in Sudan otherwise, to intervene further with expeditionary forces in order to rescue him.

Relief expeditions failed to reach Khartoum in time: Gordon and the city’s garrison were massacred. Gordon’s martyrdom inflamed public opinion and the British planned counterattacks against the Mahdi. In March 1885 an expeditionary force under General Graham was mounted, referred to as the Suakin Expedition or Suakin Field Force. With 13,000 infantry, cavalry and artillery, it was to strike from the British-held Red Sea port of Suakin and push inland, fighting Mahdist forces under the commander Osman Digna and allowing a railway to be built inland as far as the Nile, which would provide logistical support for further campaigning.

Hand-to-hand combat in the Sudan was commonplace and vicious. The Mahdists were fearless and aggressive fighters, relying on use of cover to get their massed infantry as close as possible to the enemy. Their few riflemen would soften up enemy defences with rapid fire, followed promptly by a shock charge of melee infantry in wedge formation, armed with spears and the long straight swords now referred to as kaskara. The British response to this threat was to form the trusted infantry square and bring heavy fire on their attackers, but the Mahdists disregarded casualties and successfully reached melee range on many occasions, British officers fighting with their swords and revolvers while regular infantry used their bayonets.

Graham was experienced – this was actually the second expedition he had led from Suakin against Osman – and his plan was to move detachments of his force inland toward known concentrations of Mahdist forces, and establish strongpoints in the form of zeribas (fortified enclosures made of thorn fences). If the Mahdists attacked then the zeribas would be excellent defensive positions at which to fight them, and could also become supply bases that opened the way for the British to operate further and further from Suakin itself. This tactic had merit – seven days into the campaign on the 20th March a detachment of 8,500 British won an engagement at Hashin, 7 miles inland, killing around 1,000 for a loss of 48 killed or wounded.

Graham sought to open the way to Tamai, Osman’s base 12 miles inland which was too far to be reached in one day. Around 3,000 British and Indian troops therefore set up a zeriba 6 miles inland at Tofrek on the 22nd March, but before they could finish constructing it were attacked out of the thick scrub by more than 2,000 Mahdists. The British formed squares against the oncoming enemy, some of which were briefly broken into, leading to chaotic scenes and around 70 fatalities among the British, but again much heavier losses among the Mahdists, with around 1,000 estimated killed.

Tactically the Field Force was doing quite well, winning its engagements and causing local tribes to desert Osman due to their losses, but political support for it was rapidly evaporating. With Gordon dead and the costs mounting (the railway project in particular was extremely expensive, thought to be £45,000 per mile in 1885 or £5m today) the British government, which had not wanted to fight in the Sudan in the first place and was facing a much more significant threat of war with Russia over Afghanistan, cancelled the Expedition. Graham was ordered to withdraw and his force departed from Suakin on the 17th of May.

It should be noted that none of the Foot Guards deployed with the Field Force were included in the detachments which took part in the battles at Hashin and Tofrek. We can only speculate why, perhaps Graham intended to keep them in reserve for a more major engagement. Their duties day-to-day would have been to guard the construction of the railway, experiencing low-level harassment and skirmishing by tribesmen.

I cannot therefore say with certainty that this sword was ‘combat carried’ as it does not seem the Grenadiers got to see much combat. However, it has clearly been made ready for a fight - its blade has been keenly sharpened and may have actually been resharpened, possibly multiple times as the tip section has visibly been worn down from its original contour. This would be required if, for instance, the edge had chipped or rolled and needed reprofiling.

I do not know if Ambrose also had involvement in earlier actions in the Sudan such as the Nile Expedition of 1884 (intended to relieve Gordon’s siege), in which some men of the 3rd Battalion joined other Foot Guards in a composite unit known as the Guards Camel Regiment. I can only confirm his presence among the men at Suakin, and that with absolute certainty, because while he survived the campaign and boarded HMS Tyre for the journey home with the rest of his comrades, he died en route on the island of Malta on the 25th May 1885, where he is buried with other British servicemen at Ta’ Braxia Cemetery.

With Ambrose’s death, the Goddard family estate was ultimately inherited by his younger brother Fitzroy, a career diplomat, who made considerable donations of land for Swindon’s Town Gardens, County Ground and Victoria Hospital, as well as funding its gold mayoral chain. He died with no heirs in 1927. The palatial family home The Lawn laid empty from 1931 until it was occupied by the military to billet troops during WW2, who sold the house and grounds to the Swindon Corporation in 1947, who demolished the house in 1952 and opened the space to the public as Lawn Park. The remnants of its sunken garden can still be seen in the park today, as well as the Holy Rood Church next to which can be found the Goddard family tomb.

Apart from its history this is also an excellent example of a mid-Victorian Grenadier Guards sword. The blade as mentioned is sharpened with visible sharpening marks, some small spots of light patination including at the ricasso and a few among the etching. All other metal work is bright and reflective with a small patch of cleaned light pitting on one of the lower hilt bars, and another on the outside bar next to the regimental badge. The wire binding of the grip is all intact and tight, its shagreen is excellent with no handling wear or losses. The scabbard is likewise bright with a few very shallow dents, not interfering with sheathing and drawing, and a few small spots of patination.